Fassbinder has wings, Fassbinder can fly

Text

Delia, growing up, dreamt that she would live in front of an imposing building. When she moved to Greece, years later, she realized it was the Athens Polytechnic. If you are visiting the exhibition IRL at Hot Wheels, just look out the windows: it’s there. But dreams, you know, are made of a pliable but unstable concoction: we—or even Delia, for that matter—cannot really be sure if the view outside that window is superimposable with frames from that dream. Think about it: it’d be a delicious Russian doll mindfuck. A lighting flash; coming out of oneself, levitating in someone else’s dream. An exercise that trades in lightness and transparency.

Mirrors, as we know them today, were born august cousins of that window. In the fourteenth century in Venice, artisans produced them by combining polished crystal with tin and mercury. Enormously expensive, they allowed the posh to get a hi-res idea of themselves; then they became common, witnessing us shaving, putting on makeup, practicing facial expressions. They are not transparent, their only raison d’être is to spit back light, and Rainer Werner Fassbinder loved them like a magpie. (Disco balls in Munich and New York; improvised trays for furiously ingested substances; vanity and illusion, the sound they make when they shatter.) A dark night: the state of self-imposed captivity. An exercise that trades in looping anxiety.

Fassbinder stuffed World on a Wire (1973) with mirrors: a dystopia in which computer-generated individuals live unknowingly in a forged reality, from which the protagonist manages to escape with the help of his beloved in an unexpectedly optimistic ending by the director’s standards. At the beginning of the movie, an overexcited engineer holds a portable mirror and urges a bureaucrat, “What do you see? You are nothing more than the image others have made of you. That’s all.” Hey you, yes you behind that screen—or me for that matter—does that ring a bell?

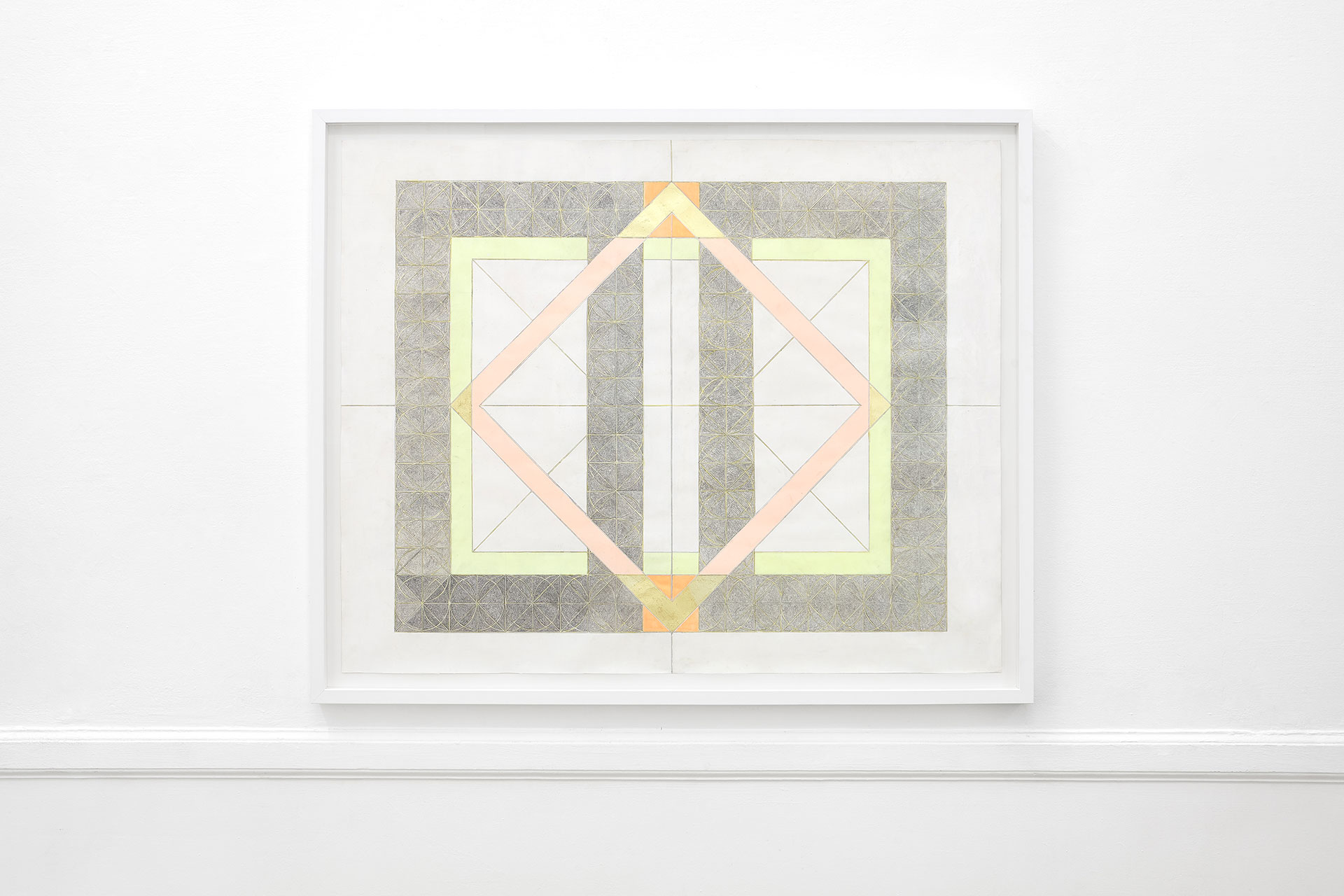

Delia Gonzalez, or her idea of art making, always stems from a desire to design transformations and to shape—however obliquely—her idiosyncrasies. This exhibition is no exception. The minimum aim is an attempt to show that Alice can cross the mirror in either direction if she wants to; to hypothesize the end of this continuous chattering; to argue that this ego—always pampered by endless solicitations, always called upon to take sides, to present itself in an ever-worn party dress—is a Sisyphean condemnation. Get in already! The seals await on the walls, the place resonates. The things you’ll encounter in the rooms are both effigies of the dark night we are trudging through together and passageways to enter a dream we have all had. Not a grandiose dream, just a shared one.

Francesco Tenaglia

Bio

Delia Gonzalez is a Cuban-American artist, musician, and producer working across film, sculpture, drawing, painting, choreography, dance and performance. Gonzalez draws inspiration from a broad range of sources including Afrocuban religion, ancient mythology, Italian architecture, cinema and different mystical traditions. Her works have been exhibited at MIT List Visual Arts Center, USA; Whitney Museum of American Art, NYC; Migros Museum, CH; P.S. 1 Contemporary Art center, NYC; Galleria Fonti, IT & Daniel Reich, NYC. Delia Gonzalez works can be seen in the permanent collections of The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), USA; MIT List Visual Art Center, USA; Warhol Foundation, USA; Migros Museum, CH; Ernesto Esposito Collection, IT; The Dakis Joannou Collection, GR; The Onassis Foundation, GR; and The Fiorucci Collection, IT.

Fassbinder has wings, Fassbinder can fly – Delia Gonzalez solo show at Hot Wheels Athens, June to August 2022 from Hot Wheels Athens on Vimeo.